The Hard Truth of Historical Accuracy

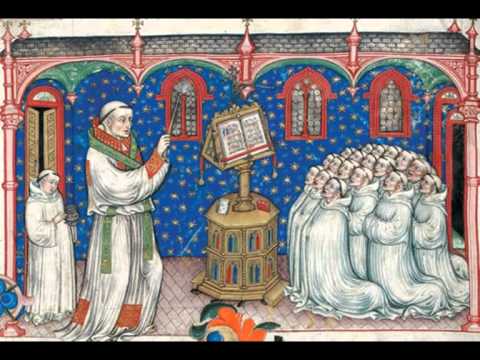

“In Gregorian Chant, art and prayer are inseparable. ... The chant cannot be sung well without prayer, neither can we pray well without singing well too.” - Dom Joseph Gajard, OSB

Introduction:

I have recently attempted to clarify my own thoughts on the issue of "historical accuracy" in Gregorian Chant... or any early music for that matter. These are thoughts I have had for many years but have always struggled to clarify them and find the right words to express them. I generally find that it is easier for me to do this in writing than in speech.

Broadening My Perspective

Over the last several years, my ongoing study and research into Gregorian chant have gradually broadened my perspective—moving beyond the relatively focused lens of the Solesmes semiology school toward a wider engagement with early manuscripts, medieval treatises, regional traditions, and the broader early‑music world (I love to nerd out on that kind of stuff). That broadening has deepened my love for chant, but it has also raised more questions than it has answered, especially around “historical accuracy” and how it actually matters in the context of the liturgy.

My Background

I have been singing chant for nearly 30 years now (since 1997), and studying it assiduously since 2005. Much of that time has been under the influence of the Solesmes school, especially in the field of Semiology (not the "Solesmes Method"). My formation has included study under the late Dom Daniel Saulnier OSB, both at the abbey of Solesmes and at Le Centre d’Études Supérieures de la Renaissance in Tours, and over the years I have also come to know Msgr. Alberto Turco and Giacomo Baroffio, who continue to act as long‑distance mentors to me. Naturally, my view of chant has been shaped very strongly by the Solesmes world of Semiology and modality.

At the same time, in the last several years I have been reading far more widely in medieval sources and in approaches that stand somewhat outside the pure Solesmes line—treatises, alternative rhythmic theories, other “historically informed” performance proposals. This has opened my eyes in many ways and confirmed that chant performance across the centuries has never been as monolithic as any one school sometimes implies. Yet it has also left me with many more questions and a fair amount of mixed feelings regarding the pursuit of “historical authenticity,” especially when we are speaking about chant in the liturgy rather than in the concert hall or recordings.

Historical Accuracy and the Church’s Own Priorities

The more I explore, the more I find myself asking what “historical accuracy” can realistically mean. We are dealing with repertories whose roots are over a thousand years old, shaped by a largely oral culture, and preserved in notations and treatises that tell us a great deal about pitch, mode, and structure, but far less about the whole sound‑world and instinctive habits of medieval singers (not to mention the entire culture, education and way of life of their times vs ours). There is a real sense in which absolute authenticity is an ideal we can approach but never fully reach. In the end, the reality is that NO ONE will - or can - ever know exactly what chant sounded like beyond the earliest audio recordings.

Then again, maybe we don't really need to either. We are not medieval singers nor can we be. We are singers of the 20th and 21st century. The people we sing for - either in concert, recordings or the liturgical congregation - are also not medieval people. They are also people of the 20th and 21st century. Singers in any of the medieval periods did not sing (as far as we know) according what they would have considered "early music" performance practices; they sang according the practice of their current time. Should we, perhaps, do the same?

I am not against singing with what we think might be medieval performance practice (all we have are descriptions, not the actual sounds); I actually find it really fun and fascinating. But I do think we need to clearly understand and admit that we are always only guessing and it also needs to be properly ordered when in the context of the liturgy.

Which brings me to my second question: beyond what is possible, what does the Church actually ask of us when we sing chant in the liturgy? In her teaching on sacred music and worship, certain constants emerge very clearly:

- The liturgy is above all Christ’s own worship of the Father, continued in His Mystical Body, ordered to God’s glory and our sanctification.

- Worship must be both exterior and interior: rites, ceremonies, and music on the outside; faith, conversion, charity, and self‑offering on the inside. Without that interior element, even the most carefully executed ceremonies and the most refined chant become empty formalism.

- Gregorian chant is given “principle place” (principem locum), named as the chant proper to the Roman Church and proposed as the supreme model for all sacred/liturgical music; the Church repeatedly urges that it be restored, taught, and actually sung by clergy and faithful.

- Music, however, is always presented as the handmaid of the liturgy. It must be holy, truly artistic, and suited to the rite; it must help the faithful to pray rather than turning the liturgy into a concert and distracting from prayer.

So when I think about how chant should be sung within the context of the liturgy, these are the coordinates that seem non‑negotiable: fidelity to the text and melody as presented in official liturgical books approved by the Holy See, a genuinely sacred and sober character, a style that serves prayer and participation, and a deep union of exterior form with interior devotion. In the context of concerts and recordings, one certainly has room to do all kinds of experimentation based academic studies.

My Own Mixed Feelings About “Historical Authenticity"

Historical research has done a great deal to challenge some relatively recent habits—rigid metrical rhythms, operatic vocalism, and so on—and it has opened up beautiful possibilities in rhythm, phrasing, and modality that make the text come alive. I am genuinely grateful for this and think it can and should reshape our practice where it clearly corrects distortions.

The Roman Church does, in fact, have an official rhythmic interpretation as presented in the 1908 Vatican Edition, and I recognize it as the Church’s normative model, even though I personally feel it sometimes lacks musicality. At the same time, back in 2018, a formal dubia was submitted to the Holy See (the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei) wherein it was asked whether it is permissible to sing chant according to rhythmic interpretive systems other than that of the Vatican Edition—specifically naming Dom Mocquereau’s method, Dom Cardine’s semiology, and even the very distinctive style associated with Marcel Pérès and his Ensemble Organum. The answer given was “Affirmative”: it is permissible to use any of those styles. Which means that while the Vatican Edition gives us an authoritative baseline, the Church does not bind everyone to a single detailed performance school in an exclusive way.

Beyond that, however, I no longer believe there is one single “correct” performance practice that all must follow under some quasi‑dogmatic obligation.

At the same time, while I don’t think we should be obsessively chasing an unreal, finally unattainable ideal of “perfect historical authenticity,” I also don’t advocate a free‑for‑all, “do whatever you want” approach either. For me, I think we can be both genuinely grounded in tradition—using what we can really know from medieval sources—while also being honest about who we are today.

How I View Different Schools of Interpretation Today

This brings me to something I need to admit: I once did fall into the attitude that I now deeply dislike. There was a time when I felt, implicitly or explicitly, that one particular method—especially the semiological approach I had received—was the only right way to sing Gregorian chant, and that other schools were simply missing the point. Looking back, I see that this easily leads into pride, narrowness, and a lack of charity.

Today, I do not claim that any one of the major interpretive schools is the uniquely “correct” one. I honestly do not think such a singular correctness exists at the level of detailed performance practice. What I do think is this:

There is a legitimate, "official" reference for the liturgy: the melodies and rules of the Vatican Edition, even if I'm not its biggest fan.

- If someone wants to sing strictly according to the rhythm of the Vatican Edition, fine.

- However, if someone prefers to follow Dom Mocquereau’s rhythm, fine.

- If someone is convinced by Dom Cardine’s semiology, fine.

- If someone follows Marcel Pérès’ more radical interpretations, or leans heavily into the writings of Jerome of Moravia, Aurelian of Reome, Berno, Hucbald, Guido or any other medieval theorists, fine.

Or, in the immortal words of Chris Farley: “Good, Great, Grand, Wonderful!” 😁

All of these approaches are, to varying degrees, grounded in historical data and serious reflection and all can argue for their own interpretation - and against all others - ad nauseam. All of them can be sung beautifully; all of them can also be sung badly.

What matters to me far more than subscribing to one “school” is this:

- Are we faithful to the received liturgical texts and melodies of the chant as the Church has given it?

- Are we singing in a way that is truly sacred, sober, and ordered to prayer? "Ut mens nostra concordet voci nostrae" ('that our minds [and hearts] may be in harmony with our voices." ~ St Benedict)

- Are we approaching the chant—and one another—with humility and charity?

- Are we living our lives in a way that is in uniformity with what the chant is meant to teach us and with the will of God?

The Hierarchy: Prayer, Virtue, and Charity Above All

This leads to what has become, for me, a constant conviction, even as my views on technical matters continue to evolve: it is far more important to pray the chant, with humility and charity, than to nail every theoretical detail of historical performance practice. A person can sing chant in a way that is historically quite imperfect and yet become a saint. Another can sing with exquisite historical plausibility and artistic genius and yet be far from God if pride, contempt, or lack of love rule the heart.

Often times, our focus on the technical aspects of chant, historical interpretation etc, can end up overshadowing the importance of praying and meditating on the texts and chants. More often than not, I will listen to chants performed by secular ensembles who sing with stunning technical perfection and yet still sound hollow and shallow because they are missing the key ingredient: Prayer.

On the other hand, when I listen to recordings of usually religious congregations singing chant, while I can recognize a lack of technical vocal mastery and "historical accuracy", it is nevertheless easy enough for me to overlook these deficiencies because I can perceive that they are primarily concerned with actually praying the chants and this also makes it easier for me to enter in prayer.

Musicality and spirituality can and should go hand in hand; there is no virtue in sloppy or careless singing. But there is an unshakable hierarchy: virtue is greater than musicality. If we lose charity—if we treat fellow Catholics who follow another school as if they were inferior, talk about them degradingly, or make chant into a tribal badge—then even the “best” interpretation has already failed at a deeper level. Charity is, in the end, the bond of perfection.

Musicology is a means to an end: the actually singing of the chant. And even the chant is a means to an end: to praise and glorify God, to unite our wills to His, become a saint and get to heaven.

So What Is “My Style"—And What Do I Teach?

If someone asks me “What is your style of Gregorian chant interpretation?” the honest answer right now is something like this:

- Historically informed, grateful and appreciative for Solesmes and semiology, but increasingly open to other schools and medieval sources.

- Respectful of the Vatican Edition as the Church’s official reference, while feeling it has limitations from a musical point of view. (Note: simply because it is the "official" rhythm doesn't mean it is the "authentic" rhythm of the 9th century or of any other particular time period. It just means that it is the "official" rhythm the Church has decided on and has yet to "officially" modify/update)

- Deeply wary of interpretive dogmatism, and convinced that multiple historically grounded schools can coexist legitimately within the Church.

- Above all, striving (however imperfectly) to place prayer, humility, and charity higher than any particular set of rhythmic theories.

What does this mean for the way I teach chant?

Since I also teach chant, it may help to say concretely what I actually teach in practice. The style I present to students can be generally summarized this way:

- Chant is first and foremost prayer. Whenever possible, one should always meditate on the text first, then study its literal/spiritual/liturgical meaning, syntax, etc. before going to the melody.

- Rhythm and melody are heavily shaped by the text: accent, syntax, and the natural flow of the language.

- The textual and melodic structure, compositional style, and liturgical function of each piece are taken seriously (e.g., difference between Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Offertory, Communion, etc.).

- The semiology of Dom Cardine and his disciples.

- Modality is approached along the lines developed by Dom Jean Claire and his disciples.

This is, in essence, the same general orientation taught at the Church’s own Pontifical Institutes of Sacred Music in places like Rome and Milan, and so in a certain sense it reflects how the Church intends chant to be learned and sung within the context of the liturgy. This framework represents a living, ecclesial approach to chant—a method rooted in research yet oriented toward real prayer and service to the liturgy.

It is not the only possible way to sing chant, and I remain open to the many voices and paths within this rich tradition. But in my teaching, I find it important to remain grounded in what the Church herself has cultivated and commended through her official institutions. It helps ensure that what I hand on is not my own invention or personal feelings, but part of an ongoing musical and spiritual heritage, approved and supported by the Church herself.

Finally, for those who are interested in the larger question of “authentic” historical performance practice, I strongly recommend Benjamin Bagby’s essay on “Reflections on the image of musical roots”. linked below. Benjamin Bagby is the founder and director of the early music ensemble Sequentia. Ever since I was a little boy I've been a big fan of Benjamin Bagby and Sequentia and I was very pleased to discover this article of his. It is a little on the long side, but very much worth reading if this topic interests you; he articulates my own thoughts on the issue of "historical performance practices" more eloquently than I ever could.

https://www.sequentia.org/biographies/background/reflections.html